Introduction to Accountability

Are you familiar with the “yeahbuts?”

It’s a popular phrase that redirects a potentially productive conversation towards a dead end.

I encountered the “yeahbuts” recently when I was talking with a frontline manager about challenges in her organization – down market, an industry being disrupted, and a new CEO who was pushing everyone to work harder/think smarter. She was in a pretty tough situation.

I tried to encourage her to think differently about the situation. Her response? “Yeah, but … (insert an excuse for why she couldn’t think differently).”

I tried to offer guidance on how she could develop new skills to respond to the challenge in her organization. Her response? “Yeah, but … (insert excuse for why she couldn’t learn new skills).”

Of course, this went on for several minutes before I changed the subject to something pretty vanilla, like, “Well, at least we’ve got some great weather in our future.”

I feel for this woman; I can recall several times in my life when I felt I was at the mercy of externalities and had little control over my situation. It takes a lot of emotional energy to redirect your attention to focus on solutions rather than problems.

That type of work, though, is the type of work that accountable leaders do. They spend time working to accept their situations and recognize that there’s an aspect of it that they can control, which is how they respond to the challenging circumstances they find themselves in.

We Can Always Be Accountable

The only thing we can control in life is our actions. Period. Within our response, we can discover accountability.

Accountability is how we respond to problems when we encounter them.

We all have problems – some we may have had a hand in creating, others maybe not. But if you’re close enough to a challenge to be aware of it, there’s always something you can do about it.

Accountability isn’t easy to express, especially when we’re stretched and challenged. In these moments, it’s easy to redirect, deflect, ignore, wait-and-see, or offer a “yeahbut” reason to why we can’t do anything about the problem we find ourselves in.

However, when we challenge ourselves and reach for accountability, we’re in a better position to lead ourselves towards a solution that helps us focus on what we can control … not what we can’t.

Accountability is in the Response – Not the Reaction

Here’s a simple equation to help you think about what you can control:

E + R = O

The Event + Our Response/Reaction = the Outcome

Consider the following situations:

If we get constructive feedback (the event), and we become defensive (the reaction), the outcome will be negative because our reaction to the circumstance isn’t productive.

On the other hand …

If we get constructive feedback (the event), and we express appreciation (the response) to the sender for offering it up, the outcome is more productive because our response conveys open mindedness to input.

Or

If we miss a work deadline (the event), and we blame any factor (unclear deadlines, another person, hefty workload), our outcome is negative because our reaction doesn’t communicate responsibility to our commitments.

On the other hand …

If we miss a work deadline (the event), and we apologize and reassure others that it won’t happen again, then the outcome is more favorable because our response communicates an ownership of our mistake.

If you look at this equation and the examples, you’ll see that we can’t control the event. That happened – whether it was our doing, or by someone/something else. We can’t control the past, yet we can spend a lot of emotional energy trying to go back in time and undo what was done or ruminate over who was right/who was wrong.

We have 100% control over our future, which can be found in the “R” of the equation – our reaction or response, which has a definite influence over the outcome.

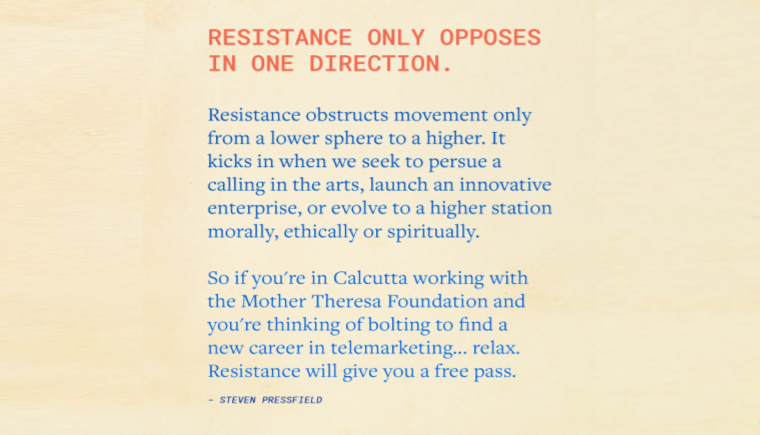

Our reaction is a knee-jerk, instinctual reaction that is primal. It’s there to protect us, whether it’s from physical harm or harm done to our ego. Our reactions can include deflecting responsibility, disagreeing with constructive feedback, or blaming others for the discomfort we find ourselves in. There’s limited growth opportunity with our reactions. Our reactions often aren’t useful or helpful, which is why they diminish outcomes to situations we find ourselves in.

Our thoughtful response, though, puts us in the position to influence outcomes and inspire others. It allows us to express our willingness to be a part of the solution as we work towards resolution and growth.

To get to a thoughtful response, though, we have to embrace a nano-second pause in our communications. This small time period allows us to think about intercepting our reactions and inserting a more productive response in their place. This is called demonstrating cognitive discipline, which means engaging our higher-order thinking skills to help us override our instincts in a challenging situation.

We learned a little bit about this when we were kids. Remember when we were told to Stop, Drop, and Roll if our clothes were to catch on fire? That was because our instincts, in the moment, wouldn’t have led us to an immediate solution if we had this challenge. This phrase was designed to help us override our thinking.

As adults, we still have the capability to do the equivalent of Stop, Drop, and Roll when we feel we’re about to shirk responsibility. When we catch our reactions and replace them, the benefit isn’t just for us, either. It’s for those around us, too.

Accountability in Leadership is Important – It Builds Trust

It takes work and intention to govern our reactions to ensure we’re replacing them with positive leadership responses. The work, though, is worth it because it allows us to build trust in our relationships because we’re reassuring others by our thoughts, words, and deeds that we want to move forward, progress, and shape our environment to one that’s more positive and productive. This is better than working in an environment where accountability is lacking; in these types of environments, we always feel uncertain … as if we’re always at risk for being the next person to be thrown under the bus.

No one wants to feel paranoid at work. We can prevent this. By demonstrating consistent accountability, we’re also influencing the level of accountability others feel comfortable expressing, too.

When we share with others where we’re wrong, accept responsibility for mistakes, or even to convey we’re not willing to blame others or things for the situation we find ourselves in, it’s refreshing. It creates a space where others can openly demonstrate accountability and share ideas on how things can be better going forward.

Five Ways to Foster a Culture of Accountability

As you seek to be more accountable, know there are ways that you can be intentional about building this skill so it positively influences the culture around you. Here are five ways to build a culture of accountability:

- Set a positive example. The best way to influence and inspire others is to teach through the example you set:-Resist the urge to blame others

-When mistakes happen, own up to them and resolve them

-Don’t focus on what you can’t control – focus on what you can

-Ensure your language is designed to unite, not alienate

-Don’t use us versus them comparisons – remember, you’re a part of the greater team and there’s no need to create factions. - Communicate clear expectations. Let people know what success looks like for them in their role. Then, if mistakes get made, you can discuss the problem and solution, while avoiding any discussion on the murky/unclear expectation (that may have contributed to the problem). The clearer you are, the more successful those around you will be.

- Let others know where they stand against expectations. The best organizations have ongoing performance-based conversations. There are no surprises to an individual’s performance because they know where they’re doing well, and they understand how they can do better. This level of candor, over time, creates safety and trust between two individuals who depend upon each other for success.

- Discuss problems openly and safely. People shouldn’t work in environments where they’re afraid to be responsible. Be the type of individual who others can approach if a problem or mistake gets made. Make sure when people bring you problems or mistakes, you keep your reactions mitigated as you think about a more useful and helpful response. There might need to be consequences for poor performance, but no one should fear the conversation.

- Focus developmental feedback on performance. Routine feedback should inspire those around you to grow. Don’t make criticism personal; focus on the behavior that can be improved as it relates to performance expectations.

Conclusion

Demonstrating accountability means relentlessly seeking ownership of mistakes, missteps, problems, and any other less-than-best outcome you are either responsible for or associated with.

To consider more ways to build your accountability muscle, watch below as SPARK author Courtney Lynch explains why accountability can be rare, and how she’s worked to meet the challenge of resisting the urge to place blame.

Join tens of thousands who are using SPARK to make a difference in their workplace and their community. Through the SPARK Experience in three easy steps, we’ll help you create a leadership development experience that will benefit you, your team, or the organization you’re a part of.